Clarifying Color-Vision Deficiency Screening

- Aug 13, 2019

- 0 Comments

by P. Kay Nottingham Chaplin, EdD

Vision screeners frequently have questions regarding when to follow the recommended manufacturer instructions for color vision deficiency screening tools. This blog is designed to address that question, and also provides a solution for color vision deficiency screening in preschool- and school-aged children beginning at age 3 years.

Vision screeners frequently have questions regarding when to follow the recommended manufacturer instructions for color vision deficiency screening tools. This blog is designed to address that question, and also provides a solution for color vision deficiency screening in preschool- and school-aged children beginning at age 3 years.Many state vision screening guidelines recommend that color vision deficiency screening follows manufacturer instructions when conducting the screening. Confusion may occur when the manufacturer instructions are written specifically for optometrists and ophthalmologists to use during eye examinations. Color vision deficiency testing in a doctor’s office differs from screening for color vision deficiencies in schools, Head Start programs, or similar settings.

Instructions for color vision deficiency testing may call for monocular testing - or testing one eye at a time with the other eye covered (occluded). When screening for color vision deficiencies in schools, Head Start, or similar programs, the screening should be conducted binocularly (both eyes open and uncovered).

This difference in monocular testing during an eye examination and binocular screening in school, Head Start, or similar settings is supported by James E. Bailey, OD, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, 2018, Southern California College of Optometry, Marshall B. Ketchum University, Fullerton, CA (personal communication, June 5, 2019).

If all vision screening for the child is successful except the color vision deficiency screening, the child should be referred to an eye doctor for an eye examination (Nottingham Chaplin, Baldonado, Cotter, Moore, & Bradford, 2018).

The eye care professional will confirm whether a color vision deficiency exists. If a child has a color vision deficiency, the eye care professional will also identify the type and severity (mild, moderate, or severe) … The eye care professional will also consult with the parents/caregivers regarding how the type and severity of the color vision deficit may affect the child’s learning, life, and career choices.

Ask the parents/caregivers to obtain a copy of the results from the eye care professional and to share those results with [school or Head Start staff, for example] because classroom and/or learning activities may require accommodations when color deficiencies are present.” (Nottingham Chaplin, et al., 2015, p. 211).

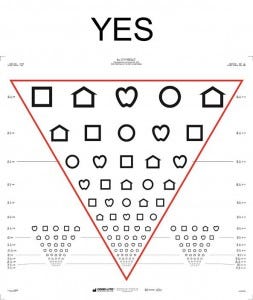

When state vision screening guidelines call for color vision deficiency screening for preschool- and/or school-aged screening, the Good-Lite ColorCheck Complete Vision Screener includes LEA SYMBOLS® for preschool-aged children and LEA NUMBERS® for school-aged children. The LEA SYMBOLS® section includes one demonstration plate and seven plates for red/green screening. The LEA NUMBERS® section includes one demonstration plate, 14 plates for red/green screening, and three plates for blue/yellow screening. Instructions are included in the Good-Lite ColorCheck Complete Vision Screener.

Screeners in a school, Head Start program, or similar setting using this book would conduct color vision deficiency screening binocularly (both eyes open and uncovered).

References:

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Cotter, S., Moore, B., & Bradford, G. E. (2018). An eye on vision: Five questions about vision screening and eye health-Part 2. NASN School Nurse, 33 (4), 210-213.

you use. Do you see the inverted pyramid or a rectangle?

you use. Do you see the inverted pyramid or a rectangle?